The abrupt school closures in Egypt mid-semester on March 15, 2020 as the result of the Covid-19 pandemic were unprecedented. No one initially knew or understood how children would complete the term, how parents of different means and circumstances would manage their children’s education from home, how end of year assignments and assessments could continue remotely[1], and how/if teachers and school communities would transition to online learning. In other words, the situation was ripe for educational research.

The Education 2.0 Research and Documentation Project (RDP) which researches and documents education sector change in Egypt, swiftly developed a pilot study, “Schooling in Egypt during COVID-19”[2] to start to interrogate the above questions. In particular, we seized on the opportunity to experiment with new and changing online tools and platforms to facilitate our remote qualitative research. In all cases, we abided by standards of research ethics and protections of subjects and their data.

Research Sampling

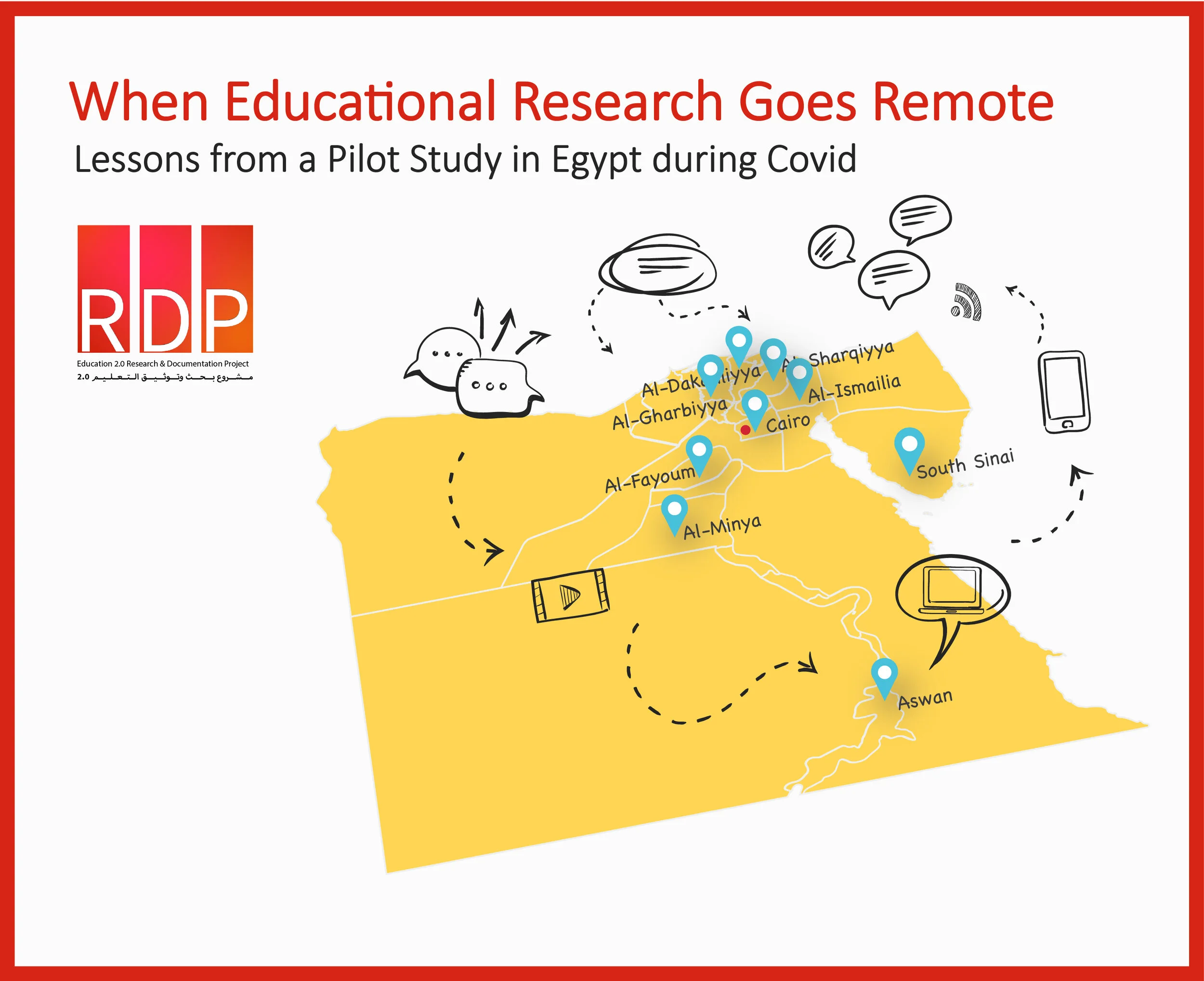

For research that aims to capture local practices, it is important to take geographic region, gender, age, social status, and access to the digital infrastructure and online resources of the Ministry of Education and Technical Education(MoETE) into consideration. Given the shortness of time and our small team of four researchers, we resorted to convenience, snowball,and purposive sampling. We reached out to different professional, family, and friend networks to create a database of over 25 parents, students, teachers and technology specialists from across Egypt. Geography was no barrier. We were able to include people from as far afield as South Sinai, Aswan, Al-Minya, Al-Sharqiyya, Al-Gharbiyya, Al-Dakaliyya, Al-Fayoum, Al-Ismailia, and Cairo, a wide range of geographic locations and settings in Egypt that would have not been possible to do face-to-face during a pandemic.

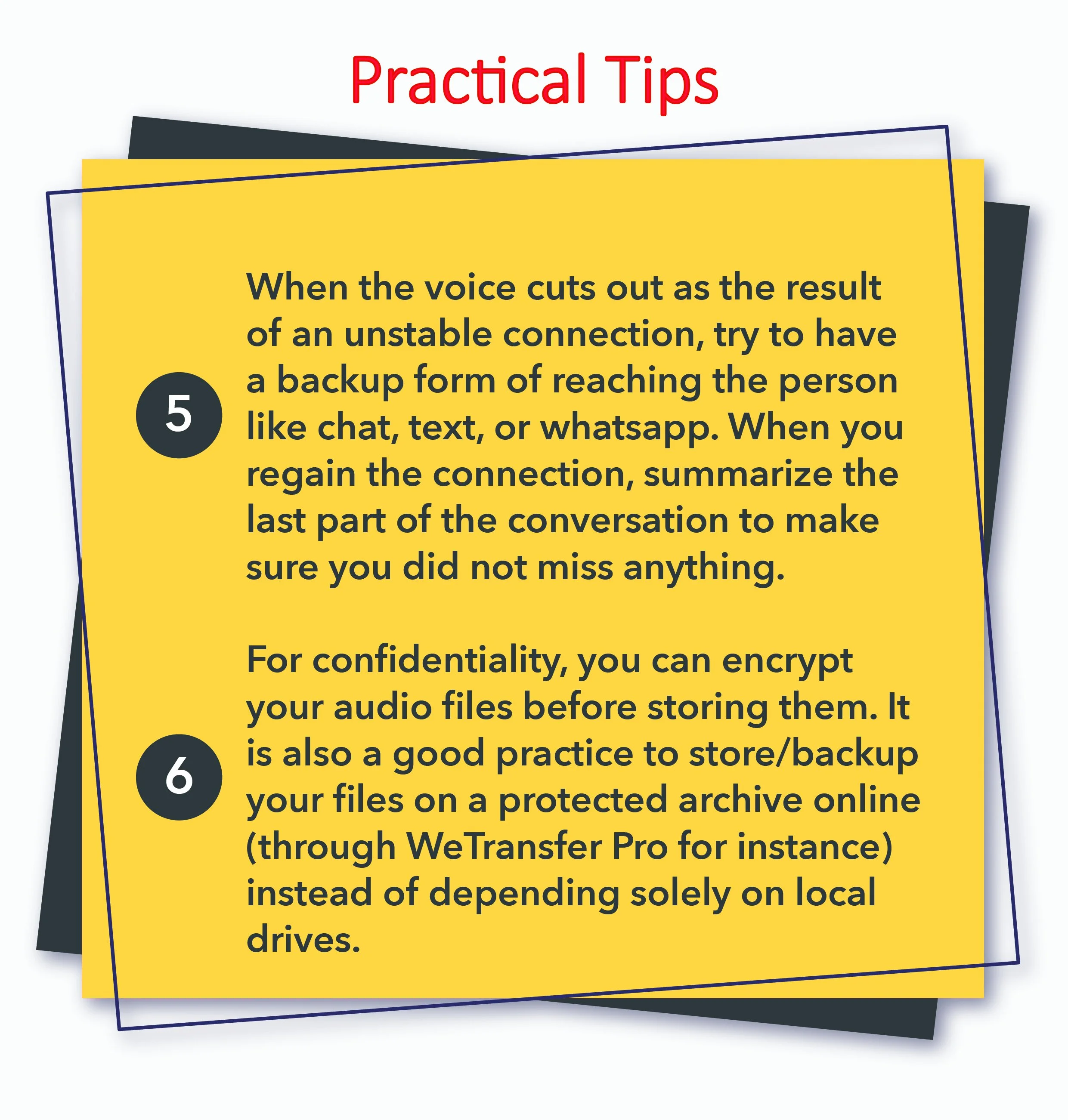

The interviews were conducted over cellular phone calls, Facebook messenger, and WhatsApp messages. An advantage to this kind of remote research is that it was flexible and easily adapted to different communication tools, however a drawback was that it favored participants with good WIFI and phone connections. This made it difficult to include information on families off the grid, with weak mobile network connections. When we could connect with them, the quality of the calls was unstable which made it difficult to have a proper and informative interview, and the frequency of calls (1 every 10-14 days) was less than the interviews with other participants (1-2 calls per week).

2. Security and Trust

Under optimal conditions, it can be difficult to gain trust with research participants. However, when research takes place from a distance, lacking face-to-face meetings, and is mediated through screens and apps, it can be especially challenging to establish trust. Some potential participants declined to participate in the study because of the remote nature of the interviews, and others discontinued after a call or two.

Teachers expressed the most hesitancy to participate over concerns that sharing their experiences and honest reflections about the Ministry’s decisions during school closures might have negative consequences on them. The research team assured them of their anonymity and explained the nature of the study. Others joined the study, but were reluctant to share their views. However, after a couple of interviews, and as the participants felt that the questions were geared towards improving the educational process and understanding their unique experiences, the participants gained more trust in the process. In some cases, they even reached out for additional calls and were eager to share additional experiences or reflections.

3. Communication Choices and Confidentiality

For remote research, one must be willing to use the communication tool that is most suitable for the participant, and when needed, alternate between different apps and platforms as the situation demands. For instance, students tended to be more comfortable on WhatsApp, Facebook, and Telegram, parents often prefered the phone or WhatsApp, whereas teachers and other professionals were happy to use Zoom and other teleconferencing sites. As with any research, one must be more careful about privacy and protection of data.

This post is part of our blog series: “When Educational Research Goes Remote”. Look out for our forthcoming blogs to find out how oral history and social media documentation were used in this pilot research. (The actual findings from the research are underway).

[1] A Ministerial Decree under No. 70 of 2020 was issued on March 30, 2020, declaring that the end of year assessments for the academic year 2019-2020 include research projects for students in primary and preparatory years from grades 3-9, and take-home online tests for secondary school students in grades 10 and 11.

[2] The final research outcomes of the "Schooling in Egypt during COVID-19" pilot study are still under development by the RDP team.

We would like to express sincere gratitude to our colleagues Nairy AbdElShafy, Hany Zayed, and Ahmed Sharaf who provided insightful comments on an earlier draft of this blog.

Photo designs by: Heba Shama

Photos attribution: <a href="https://www.freepik.com/vectors/background">Background vector created by rawpixel.com - www.freepik.com</a>

<a href="https://www.freepik.com/vectors/background">Background vector created by freepik - www.freepik.com</a>

[To cite this blog] Herrera, L., and Shama, H. “When Educational Research Goes Remote: Lessons from a Pilot Study in Egypt During Covid-19” Education 2.0 Research and Documentation Project (RDP). August 28, 2020. https://www.rdp-egypt.com/en/newblog/remote-research-during-covid-19/